|

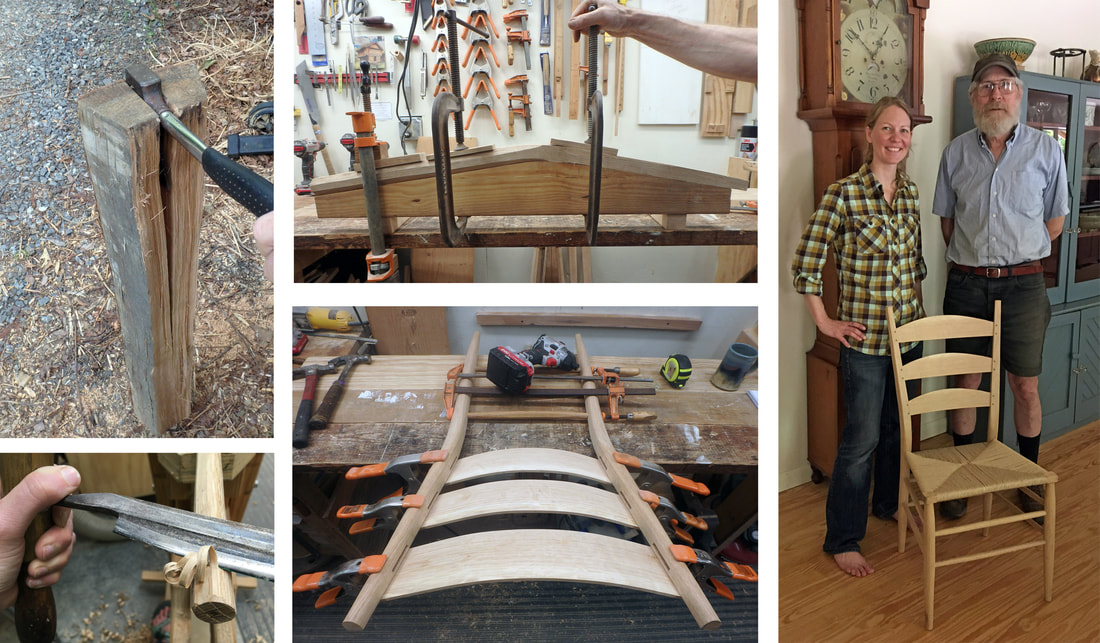

Throughout my time as an artisan, people have often asked if I’ve been certain places or met specific people based on the products they see me make. Over the past few years I’ve been compiling lists – moving places a notch higher in priority as more and more people mention them to me and becoming more interested in meeting or working with a specific person as I continue to learn how much we have in common. This past winter, I decided that my list had gotten long enough that it was time to do something about it. I had amassed a page-long list of places and people in the southeast US and I figured out a route that would take me on a big loop visiting almost every one of them. And so, in mid-May I drove away from the rocky shores and trees with branches still bare and headed towards the coves, gaps and ridges of the Appalachian Mountains, where “Boiled P-NUTS” are sold on the roadside and billboards ask “Do you have the Black Lung?” to advertise for the local attorney. My first night in Appalachia was spent with Drew and Louise Langsner at their home and the former home of Country Workshops. I was less then ten steps from my truck when Louise was already embracing me and showing me to my room upstairs in the barn. We climbed the stairs to a storage area packed full of slab wood and willow, where off to one side there were two bedrooms and a bathroom. The first room was occupied by Drew and Louise’s friends from Brasstown, NC (and frequenters of North House Folk School!), while I was shown to the second, a plain room with a lovingly worn Tree of Life quilt on the bed and screenless open windows looking over their gardens and the expansive Appalachian Mountains beyond. While I unpacked a few items from my pack basket and settled in, Louise headed down to the garden, already seeming in full summer splendor, and picked a jar-full of flowers for the porch table where most of our time that evening would be spent. Their home was as dreamy as I could have imagined – the hand-hewn dovetail log cabin was filled with handmade baskets, coopered buckets, carved and turned bowls and spoons, post and rung chairs, and books. We were a group of seven for the evening and enjoyed home-cooked food on the back porch under the spreading trees where fireflies flickered, and we talked of craft, books, movies, rural health care and Drew’s close call with jail (who knew AAA coverage includes Arrest and Bail Bonds?!). While visiting, I had the pleasure of coming across a dustpan that Drew made many years ago and has been obviously well-used as it is now almost as much duct tape as it is wood! When I commented on it and took some pictures, Drew sheepishly said that he needs to make another. I fawned over his collection of small hand-brooms, perused his collection of butter spreaders from all over the world, held spoons made by Wille Sundqvist, and chatted about the evolution of a bowl carver. My time there was full but short, as many adventures still awaited, and I drove away inspired and excited. I then visited Penland School of Crafts and Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts and continued on to spend a few days in and around Asheville exploring the many folk arts centers and galleries. One location that was on my list was a place called Grovewood Village. I didn’t have any notes or memories about why exactly I wanted to visit this place, but there I went. As I drove in and parked, I started to get confused about why exactly I was there – I was surrounded by careful landscaping, a contemporary sculpture garden, grandiose buildings, and a fancy golf course and clubhouse….. The sign for Grovewood Gallery caught my eye, so I popped in, but was uninterested in the pricy contemporary art and polished furniture. After leaving the gallery, a small, unassuming sign on a building sandwiched between the gallery and the Antique Car Museum caught my eye – Homespun Museum. I stepped in past a sign that advertised a once daily tour at 1 pm (it was about 12:40 then). It was here that I found what I was looking for. The small one-room museum was packed full of information about Biltmore Industries, an arts and crafts enterprise that started from a small craft education program in 1901. As the story goes, while visiting Asheville for the summer, Charlotte Yale and Eleanor Vance (who had formally studied woodcarving at the Art Academy of Cincinnati) began teaching young boys from the area how to carve wooden bowls and picture frames. The local Vanderbilts then got involved and, to make a long story short, helped the school grow to include a weaving studio, which by the late 1920s employed 75-100 workers and produced 950 yards of fine homespun fabric every day. Though woodcarving and furniture building continued to be a part of the story, the weaving of homespun fabric is what brought most of the fame and fortune. Customers included Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, Helen Keller, Franklin Roosevelt and Eleanor Roosevelt and orders for the fabric came in from across the country and globe. It wasn’t until the 1980s that the last loom was taken out of service as the industry succumbed to modern weaving factories. As part of the tour, we went into the Dye House, which is partly preserved almost unchanged from the day the weaving stopped (there was even still wool in many of the industrial carders) and is partly a warehouse-like dumping ground of all the disassembled loom parts and unused equipment. What a unique little gem in such an unexpected place! And I love that it all began back in 1901 with a woman teaching woodcarving! Though I did wonder why, according to the information I read, she was only teaching woodcarving to the boys… The next part of my journey took me to Brasstown, NC, home of John C. Campbell Folk School and a small mecca of highly skilled craftspeople. I was there to spend a week with Tom Donahey, who is a master chair-maker and general woodworker of all sorts. Tom is one of the reclusive geniuses of the craft world who is nearly unknown in the technological world of the internet and social media. Now days, all his chair clients are through word of mouth, and he has no interest in having an email address or posting anything online. When I was an intern at John C. Campbell a little over two years ago, I spent a week with Tom building one of his chair designs, which he refers to as a “Classic Mule Ear,” a post and rung chair that is an upscale version of Jennie Alexander’s “Peoples’ Chair.” I left my last chair-making experience with my chair and a chair-stick (a measuring tool with marks along it referencing the locations of all of the tapers, mortises, and angles found on a chair), which in theory was all I needed to go home and make another. It’s the “in theory” part that got me good. I was in need of a second round. Tom and his partner Linda warmly welcomed me into their home (which I played a small role helping build back in 2014), and for a week Tom and I worked in his shop, not only building chairs, but making notes, drawings, photos, videos, and talking some pretty deep chair and wood theory. We spent our time splitting out chair pieces from an oak log, steam bending rear posts, using spokeshaves, drawknives and sloyd knives to shape pieces, and whacking things together with heavy mallets (and I won’t deny that we did also use some power tools). Most people who build a chair with Tom just want to build a chair, so I think my questions and view points were refreshing to Tom since they came from a place of not only wanting to replicate what we were doing but wanting to understand why we needed to take the steps to do what we were doing. In the process of building these chairs, one of the steps is to put the rungs in a kiln to drive out moisture thereby reducing them to their smallest possible size, so once seated in their mortises, they will expand and create more permanent joinery. As a result of thoughtful conversation, we decided to test to see how long it actually takes a kiln-dried rung to expand back to full size. Tom has always felt a certain amount of haste was necessary when assembling the parts of a chair because in his mind, the rungs would start expanding as soon as we took them out of the kiln. So we took one out, measured it to ten thousandths of an inch both along the rings and across the rings, and put it aside to check again every few hours. We found that the growth in the first six hours was negligible and that it took almost two full days of the rung being out of the kiln to reach full-size in the humid Appalachian climate. So now we know we can take our sweet time (which was useful knowledge as Linda came in to visit just as Tom was assembling his chair and he didn’t need to get stressed!). The rest of the week was filled with similar testing and idea swapping, and I left with a chair, another chair-stick, 35 pages of handwritten notes, and my mind filled with all sorts of new understanding about wood and carving and life. I even got a farewell supper of squirrel stew, maybe not quite as Appalachian as opossum stew, but it did the trick. With my belly full, I traveled on to Berea, KY, home of Berea College. Since 1859 Berea College has had a unique approach to higher education, having the goal of making it more accessible by having students participate in work-trade for their tuition. One department where students can work is Student Craft, where they can participate in woodworking, broom making, weaving, or ceramics. Upon arriving on campus, I stopped by the Log House Craft Gallery, which sells crafts made by students and other local artisans, before walking across a field to the building that houses the woodworking and broom making programs. Being summer break, there was only one student working in the broom shop, which normally employs up to ten students. Chris, who runs the broom making program, was there in the shop, and he gave me a tour while we talked more about how the Student Craft department works and the business of broom making. It is my understanding that the Student Craft department has been facing some challenges as administration is trying to focus on more “relevant” ways for students to contribute and gain skills for life in the modern world, and as it loses money on the high overhead and declining sales. Amidst stories of struggle, however, there were also some hopeful stories. The woodworking shop, which in the eighties largely converted to CNC machines and plywood construction, recently built six shaving horses, and it is now not uncommon for visitors to the shop to see student working with spokeshaves, shaping parts for use in stools or baskets. It was really interesting to learn more about this program and see traditional craft in a college setting, and I’ll be interested to continue following the evolution of Student Craft. They have a great Instagram feed @Berea_College_Crafts for those interested in following this program. I had many other amazing experiences, learning from makers, gaining inspiration from museums, and conversing about craft, philosophies and lifestyles, but I’ll spare you the rest of the details for now!

1 Comment

|

Marybeth GarmoeCraftsperson Archives

August 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed